The Book of Common Prayer is a devotional guide (and so much more) for those of the Anglican (Episcopalian) faith, developed by the key historical figure in Anglicanism, Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury.

My own introduction to The Book of Common Prayer was through a textbook assigned in graduate school, Worship by the Book. Worship by the Book was edited by Dr. D.A. Carson, Research Professor of the New Testament at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School (Deerfield, Ill.). He is considered to be one of the preeminent biblical scholars of his generation. By way of contribution to Worship by the Book, Carson (Evangelical Free Church) contributed the first chapter as well as served as general editor of the book. Other authors – each notable in his own tradition, if not worldwide Christendom – included the late Mark Ashton (Anglican), R. Kent Hughes (Free Church), and Timothy J. Keller (Presbyterian). I highly recommend this book, especially for the first chapter by Carson and the chapter by the late Mark Ashton.

The Rev. Mark Ashton (1948-2010) was assisted by C.J. Davis to pen his chapter entitled “Following In Cranmer’s Footsteps,” which is the focus of this paper. Ashton’s obituary referred to him as “one of the most influential evangelical pastor-teachers of his generation.” Neither Ashton nor Davis were far-removed from the pew as they were both actively pastoring Anglican congregations at the time of writing. This anchors the essay in practical discussion, rather than theory (Carson’s preceding chapter can be considered a theoretical/theological framework for the book).

Thomas Cranmer is a foundational figure for the Anglican faith. While Henry VIII may have been the founding potentate of said church, Cranmer was the architect of Anglicanism’s schism from Rome and its guiding light until his death in 1556. It was Cranmer who sought to raise English support at Cambridge for the royal annulment and Henry’s (re)marriage to Anne Boleyn, and who – when Rome refused – granted the annulment against Catherine (he would later grant Henry a second annulment and third marriage to Anne of Cleves). He was able to execute these actions as the Archbishop of Canterbury, a position to which Henry helped him to be elected in 1532. In many ways, Cranmer stayed loyal to his royal patron (he was a believer in the divine right of kings), though the churchman was also granted great freedom to expand and explore his own theological conscience. Among Cranmer’s greatest goals was the Anglicization of the church. He did not believe that Rome, its operatives, traditions, and language could meet the gospel needs of England (he also developed the notion that religion should be accessible to all the people, not just the theologically educated academy). Pragmatically he became aligned with the Protestants, even for his rejection of the Rome-centric nature of Roman Catholicism. It was in this area that Cranmer is most remembered for his contribution to Anglicanism – an English-speaking Christianity. In 1550 Cranmer released The Book of Common Prayer, a prescriptive manual to the liturgy of the Church of England (and, in revision, has come to include Articles of Faith). The basic authoritative edition used today dates from 1662. In an article entitled “Unmatched Masterpiece” (Christian History Magazine, 1995), Roger Beckwith notes the following tasks which Cranmer assumed in creating The Book of Common Prayer, “First, these services needed to be translated from Latin into English. Second, unscriptural teaching needed to be replaced by biblical teaching. Third, he wanted to simplify and condense the five medieval manuals of worship into one volume. Finally, he wanted to revive the regular, orderly reading and preaching of the Bible.”

Before his death at age 66, Cranmer’s fortunes fluctuated with the throne. His anti-Catholic sentiments were severely curtailed when Mary Tudor (the vindictive, Roman Catholic daughter of Henry and the scorned Catherine) rose to power in 1533. Predictably, Mary had Cranmer executed (burned) as a heretic. In the trial that surrounded his death, he was subjected to a forced recantation of his pro-English / anti-Roman Catholic beliefs. Even with such a repudiation of his Protestant leanings, his death at the stake was assured. At Cranmer’s final – public – recantation (held at the University Church in London), he was to read a pre-approved, pro-Roman Catholic message. However, at the close of his statements, his conscience was thought to spring to life for a final surge of theological independence as he recanted his recantation, saying, “And as for the Pope, I refuse him as Christ’s enemy, and Antichrist, with all his false doctrine.” With his conscience once again speaking clearly, Cranmer surrendered to his doom. For the sinful activity of his hand (writing out the now-invalidated confessions of heresy), he offered first his hand to the flame with the words, “…forasmuch as my hand offended, writing contrary to my heart, my hand shall first be punished therefor … this unworthy right hand … hath offended” (p. 603 in Thomas Cranmer: A Life by Diarmaid MacCulloch; New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1996).

Although Cranmer’s voice was silenced, his writings lived on. The Book of Common Prayer has had an enduring effect on the Anglican Communion and its members, some 85,000,000 in several daughter churches, including the Churches of England, Nigeria, Uganda, Kenya, Sudan, the church of South India, the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America (“Episcopalians”), and many others. Anglicanism is the third largest branch of traditional Christianity (behind Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy). The expansion of Anglicanism is due in no small part to the world-spanning British Empire, which exported its faith with considerable missionary vigor. Though all of these national and localized churches have considerable freedom from Canterbury, they all employ the Book of Common Prayer as a unifying force in ritual, liturgy, and theology. Although there are alternative worship guides and prayer books, at Anglicanism’s core is Cranmer and the Book of Common Prayer.

Cranmer’s Achievement

Ashton and Davis argue that Cranmer’s major achievement was not penning the august words of the Book of Common Prayer, but rather using his own writing to connect people to the God-breathed Scriptures. A three-point matrix is set forth, embodying Cranmer’s own guiding principles, which the authors believe would connect people to the God-empowered Scriptures today, much like the Book of Common Prayer did when it was originally composed. The three points are that the liturgical and teaching program be biblical, accessible (to the common man), and balanced (not formulaic, nor far-removed from the human heart, but in-tune with the frailties of humanity). “So Cranmer’s legacy is a sound biblical theology, combined with a moderate and common-sense theological pragmatism expressed in a liturgical tradition that has frequently strayed from its founder’s ideals, particularly in recent years, but is still relevant” (Ashton 76).

Our Responsibility

Ashton and Davis note that Anglican law gives local clergy much leeway when making the best decisions for the local parish. It is, therefore, incumbent upon these ministers to take the best of the Anglican heritage and build upon it, rather than lose it. “When it was written, the Book of Common Prayer represented an attempt to make culturally relevant and accessible the uniform truth of the Christian faith” (Ashton 78). The balance of this section is a plan for reimplementing the Book of Common Prayer – or at least the guiding principles by which it was written – into the life of the Church of England and the rest of the Anglican Communion. “We will want to maximize the intelligibility and develop the corporateness of the service” (Ashton 79).

In Practice

“Good services require planning, and that requires time” (Ashton 80), though the authors are not advocating a rigid return to Anglican liturgy. There is no desire to “stifle creativity and imagination,” but a pursuit of excellence.

“If it is ever to play a part in English national life again, the Church of England has to recover its spiritual reason for existing. God has promised to bless the preaching of Jesus Christ. He has not promised to bless denominational distinctive. If Anglicans continue to preach Anglicanism and not the gospel, Anglicanism will continue to die. But if as Anglicans we preach the gospel, the Church of England may yet have a future in the purposes of God” (Ashton 108).

With that powerful of a statement, the authors have pledged more allegiance to the biblical church than the church defined in detail by Cranmerism or the Book of Common Prayer. It is with this cheery hope – and solemn warning – that the authors conclude their chapter, once again making a compelling case for the three-fold rubric for planning and evaluating church assemblies:

Questions to ask if we are to follow in the noblest of Cranmer’s footsteps:

“Is it biblical?”

“Is it accessible?”

“Is it balanced?”

Oh ho! A box, delivered from ye olde England? What would Her Majesty be sending to me?

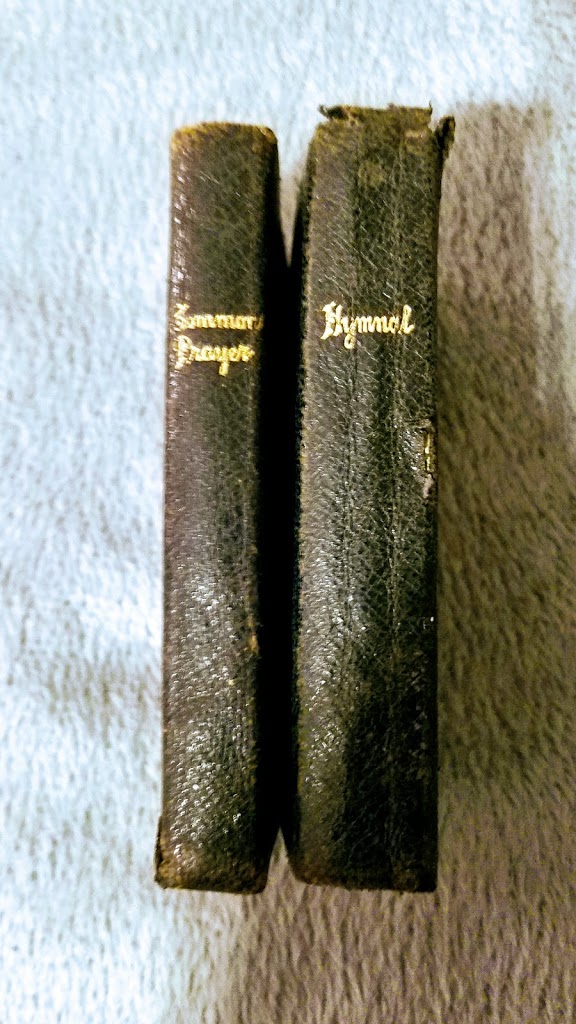

Not only books – of course books – but books in a wee leather case!

Two books, so very small. This set of two, together in a case, was published in 1890 (128 years ago). Cover pages to follow in album.

The Hymnal Companion to the Book of Common Prayer (Third Edition). London, 1890. Front cover

The Hymnal Companion to the Book of Common Prayer (Third Edition). London, 1890. Title page

“The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacaments, and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, According to the Use of the Church of England; Together with the Psalter or Psalms of David, Pointed as They Are to be Sung or Said in Churches; and teh Form and Manner of Making, Ordaining, and Consecrating of Bishops, Priests, and Deacons.” London, 1890 Front cover

“The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacaments, and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, According to the Use of the Church of England; Together with the Psalter or Psalms of David, Pointed as They Are to be Sung or Said in Churches; and teh Form and Manner of Making, Ordaining, and Consecrating of Bishops, Priests, and Deacons.” London, 1890 Title page

“Book of Comon Prayer” and “Hymnal,” 1890, spine.